I’ve delved into the ever-changing nature of languages a little before on this blog (see here) but a chance find in a Welsh charity shop, for the bargain price of 50p I might add, has had me swimming back upstream into the earliest origins of the tongue I know best.

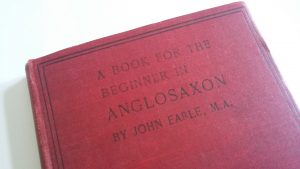

A book for the beginner in Anglo-Saxon is a revelation. Published in 1902, the front page of my now treasured copy has a sticker in it indicating it once belonged to the library of the Girls Intermediate School in Llanelly.

A book for the beginner in Anglo-Saxon is a revelation. Published in 1902, the front page of my now treasured copy has a sticker in it indicating it once belonged to the library of the Girls Intermediate School in Llanelly.

In today’s world we can hardly imagine such a book in a school library, never mind the subject possibly on the curriculum, but why wouldn’t we be interested in the history of the language we speak?

The furthest back most of us delve at school is usually Shakespeare, who wrote in the late 16th century, or perhaps Chaucer, writing some 200 years earlier, and already, for me at least, it was more taxing than a foreign language. You can kind of get the gist of what’s going on but the effort to understand it is considerable.

Growing up, the big event in my small home town, apart from the very exciting annual fun fair, was the staging of a Shakespeare play every year in the ruins of a Norman Castle. As you can imagine, every school ensured that we were exposed to this cultural spectacle from an early age. A bit too early, I would say.

The fact is, Shakespeare is a hard gig, and Chaucer is borderline impenetrable. To go back a further 600 years would surely reveal a language unrecognisable to the modern English speaker.

So, even though I’ve had the odd brush with Latin and Greek in my time, I suspected my whim of tackling Anglo-Saxon in my later years would prove to be a recipe for crushing boredom.

I couldn’t have been more wrong. Now I didn’t set about the task of learning Anglo-Saxon, that would be going a bit far, just reading the book.

What interests me is the connections with today’s language, the ghostly traces of an ancient language still casting its shadow over modern parlance, the half-remembered words spoken by the old folk of my childhood. That sort of thing.

Well, it is not as inaccessible as you might think. Lots of words have come down to us in a completely recognisable form, with perhaps a tweak in the spelling. The word word itself for example.

A leaf on a treow, the cealf and lamb in the fields, even the graes-hoppa, and, when we know that ‘c’ is a ‘ch or ‘sh’ sound, we can understand that a sceap is a sheep.

A hand, an eare, a tunge and a lunge help us appreciate the wunder of lif. With ‘g’ sometimes pronounced as a ‘y’, daeges and nihtes is understandable.

A couple of funny letters – a sort of p called ‘thorn’ and a squiggly d, both sound like th. So what looks like ping is that ever useful English staple, thing.

A couple of funny letters – a sort of p called ‘thorn’ and a squiggly d, both sound like th. So what looks like ping is that ever useful English staple, thing.

And then there’s the family, moder, faeder, cild, or, familiar to those in the north or Scotland, bearne, and brodor, sweostor, sunu and dohtor.

There are so many examples, god (good), betera and betst and yfel (bad, or evil?) wyrsh and wyrst I could give any number of examples from six to twentig or even fiftig, I just don’t cnawe when to stop.

The conjugation of verbs is a minefield of complications of the ‘swim, swam, swum’ variety, but it is easy to see the modern word from the infinitive (‘to’ form, e.g. to go, to think, etc.) such as cuman (to come) metan (to meet).

Faran or gangan mean to go, and hence we bid farewell to those that are going, and wendan means to wend, for wending our weary way home. In the past tense, I wend becomes I went, so somewhere along the weary way gangan and wendan got mixed up.

Acsian or axian is to ask, and is still pronounced in the old way, ‘aks’, in corners of the south-west Midlands and beyond, all the way to the West Indies.

Weaxan means to grow, which explains why the moon waxes and wanes.

Many words, on closer examination, don’t seem too far from the modern language. Ham means home… and finds its way into hundreds of place names, and even my own surname.

Adl means disease, so if your brain is feeling a bit addled reading all this, it could be worse than you think.

If you finde all this interesting and want to grafe (dig – from whence we get graft) a lytel deeper, freonds, I haebbe just the book to helpe.